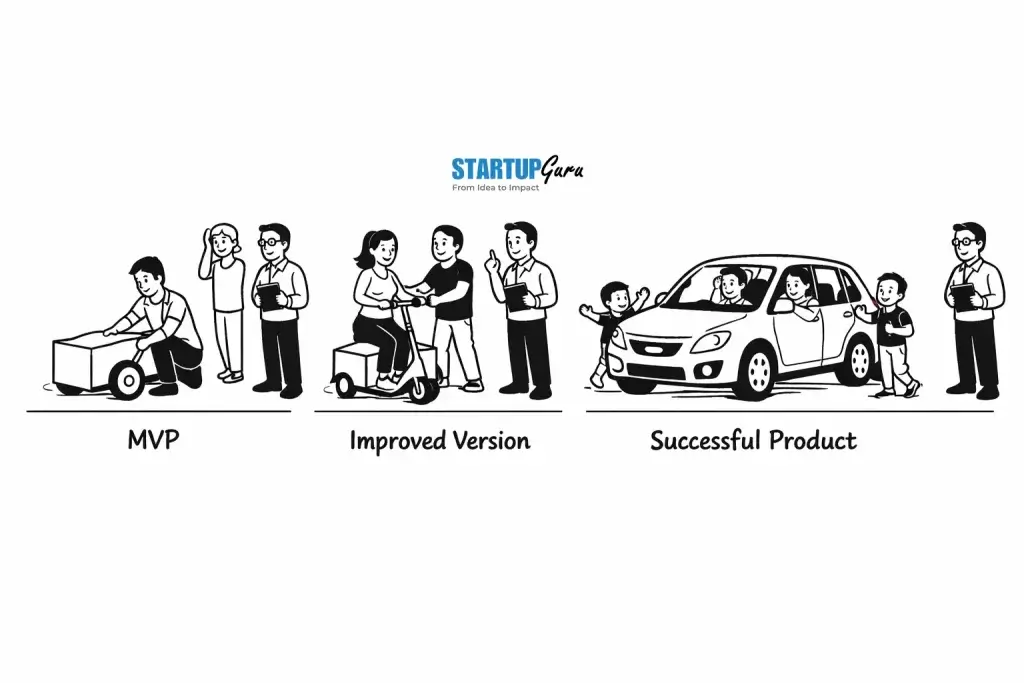

Let me start by clearing up a misconception I see all the time. An MVP is not a cheap version of your final product.

It’s also not a half-baked product you ship because you ran out of time or money.

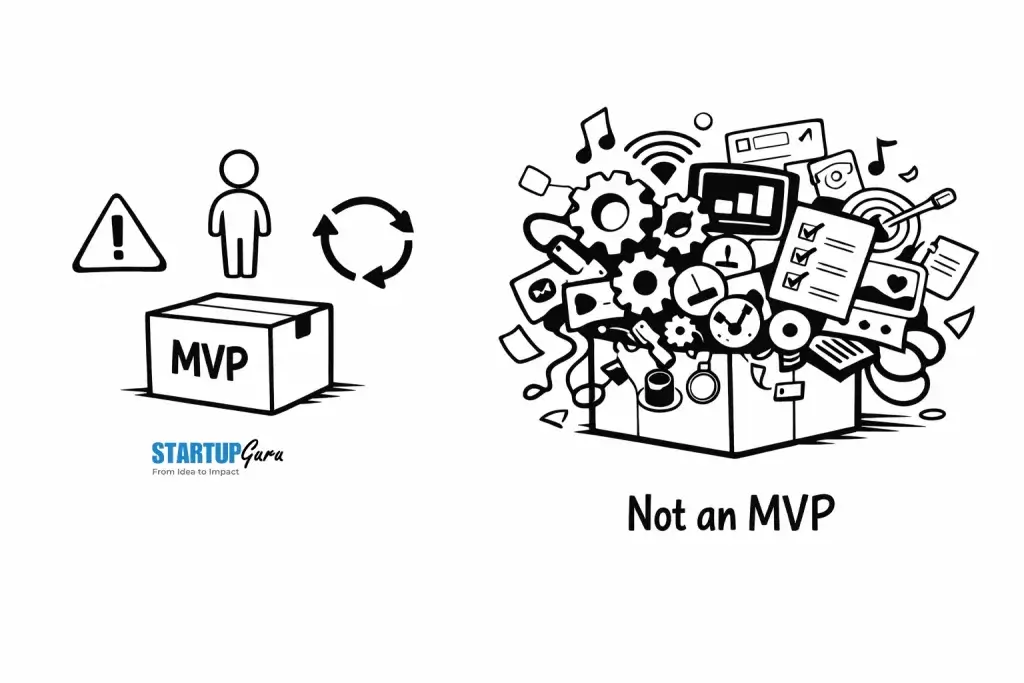

An MVP, or Minimum Viable Product, is the smallest version of your product that can be used by real users to validate a real problem.

That’s it. No fluff.

When I explain this to founders at StartupGuru, I usually put it this way:

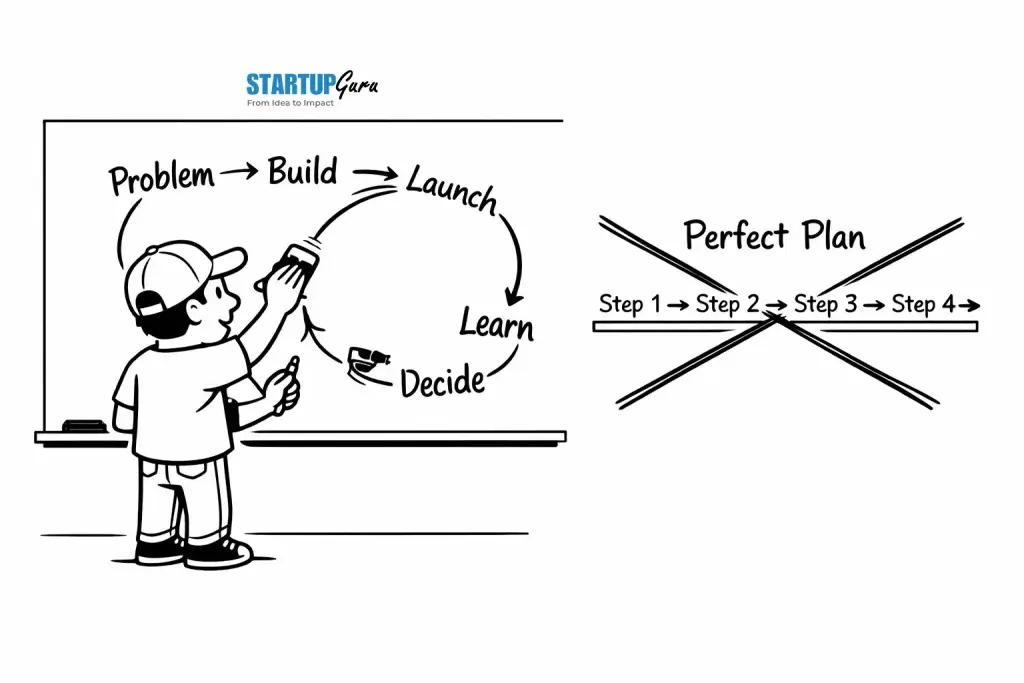

An MVP is a learning tool, not a delivery milestone.

The goal of an MVP is not scale, polish, or feature completeness. The goal is evidence. Evidence that someone other than you actually wants what you’re building, and is willing to use it, pay for it, or at least change behavior for it.

Eric Ries, who popularized the concept through The Lean Startup, defines an MVP as a version of a product that allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning with the least effort. That framing still holds up today, even with all the tooling we have now.

In this post, we'll cover:

- 0.1 Minimum Features + Real Users (This Part Is Non-Negotiable)

- 0.2 MVP vs Full Product (Where Founders Go Wrong)

- 1 Why MVP Is Important for Startups

- 2 Key Characteristics of an MVP

- 3 MVP vs Prototype vs Proof of Concept (PoC)

- 4 Types of MVPs

- 5 MVP Development Process (How We Actually Do It)

- 6 MVP Success Stories (What Worked and Why)

- 7 When an MVP Is Not the Right Choice for Your Startup

- 8 How to Measure MVP Success (What Actually Matters)

- 9 Frequently Asked Questions About MVPs

- 9.1 How small is too small for an MVP?

- 9.2 Should an MVP be built only for early adopters?

- 9.3 How long should MVP development take?

- 9.4 Can an MVP be no-code or manual?

- 9.5 Do investors expect a polished MVP?

- 9.6 Should I include pricing in my MVP?

- 9.7 When does an MVP stop being an MVP?

- 9.8 What’s the biggest MVP mistake founders make?

- 10 Take away

Minimum Features + Real Users (This Part Is Non-Negotiable)

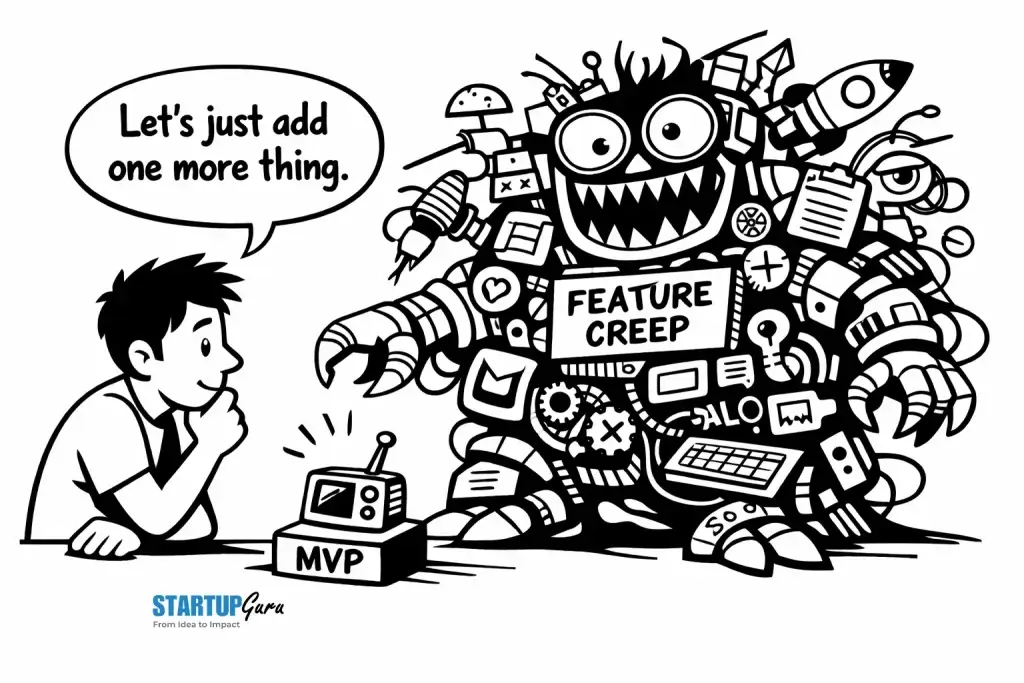

Two words matter more than anything else in MVP: minimum and viable.

Most founders obsess over the minimum. Very few respect viability.

Minimum means:

- You deliberately cut features.

- Resist the urge to “just add one more thing.”

- You focus on solving one painful problem, not five nice-to-haves.

Viable means:

- Real users can actually use it.

- The product does something meaningful for them.

- You can observe behavior, not just opinions.

If no real user is touching your MVP, you don’t have an MVP. You have a prototype sitting on a server.

At StartupGuru, and our partners at NCrypted, this is one of our hard rules:

If it cannot reach real users within weeks, we push back on the idea.

I’ve seen founders build technically impressive products that took six months to ship, only to realize they were validating assumptions instead of demand. That’s not an MVP. That’s expensive guesswork.

Dropbox is a classic example here. Their MVP wasn’t a full product. It was a simple explainer video that demonstrated the core value. That video validated demand before heavy engineering investment.

The key takeaway:

Your MVP must be something users can react to with their actions, not just their words.

MVP vs Full Product (Where Founders Go Wrong)

Another trap I see founders fall into is treating the MVP as Phase 1 of the final product roadmap.

That mindset is dangerous.

MVP is NOT your Phase 1. Repeat – Your MVP is NOT YOUR PHASE 1.

I find it worrying that most founders still get it wrong. This is why we developed the MSP concept in our incubation program for non-tech founders. We call it your Minimum Sellable Product. When we attach the “sellability” factor to “viability”, founders get the point. Don’t get excited yet. It still takes us a full 4 months to convey this point. 😀

Learn more: MSP vs MVP

A full product is built for:

- Scale

- Edge cases

- Performance

- Reliability

- Brand trust

- Long-term maintainability

An MVP is built for:

- Speed

- Learning

- Validation

- Directional clarity

These are opposing goals.

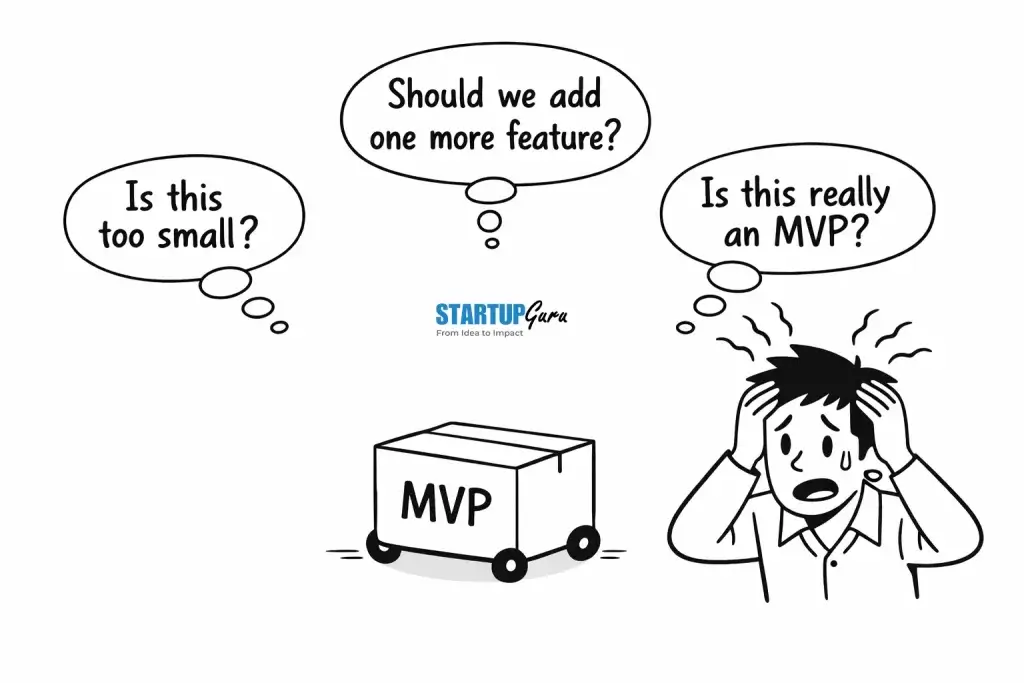

When founders say, “Let’s build the MVP properly so we don’t have to redo it later,” what they usually mean is, “I’m uncomfortable shipping something incomplete.”

That discomfort is natural. But avoiding it defeats the purpose.

At StartupGuru, we actively avoid overengineering MVPs. We choose speed over elegance, clarity over completeness, and learning over perfection. If the MVP breaks some assumptions or forces a rewrite later, that’s not failure. That’s success doing its job.

A full product answers:

“How do we scale this business?”

An MVP answers:

“Should this business even exist in this form?”

If you blur that line, you risk spending months solving the wrong problem beautifully.

Why MVP Is Important for Startups

If I strip away all the theory, frameworks, and buzzwords, this is the real reason MVPs matter for startups:

You are wrong more often than you think.

And the faster you find out how you’re wrong, the higher your odds of surviving.

I’ve worked with first-time founders, repeat founders, and operators coming out of large companies. The pattern is always the same. Everyone starts with strong convictions. Very few start with validated truth. An MVP is how you bridge that gap without burning your runway.

MVPs Reduce Risk (The Right Kind of Risk)

Startups don’t fail because founders don’t work hard. They fail because they spend too long building things nobody truly needs.

An MVP reduces product risk, not by eliminating uncertainty, but by exposing it early.

Instead of betting everything on a fully built product, you’re placing small, controlled bets:

- Will users care enough to try this?

- Will they come back?

- Will they pay or at least engage consistently?

We’ve seen founders de-risk ideas in weeks that would have taken months otherwise. We intentionally design MVPs to surface uncomfortable truths early. That’s the whole point. If your MVP only confirms what you already believe, it’s probably not honest enough.

MVPs Save Time and Money (Because Waste Is the Real Enemy)

Time and money are not separate constraints in a startup. Time is money.

Every extra feature you build before validation compounds the cost:

- Development cost

- Maintenance cost

- Cognitive load

- Decision paralysis later

An MVP forces ruthless prioritization. It asks one brutal question:

What is the smallest thing we can build that still teaches us something useful?

This is where many founders struggle emotionally. Cutting features feels like compromising the vision. In reality, it protects it.

This is something we actively avoid:

Building “future-ready” MVPs loaded with hypothetical features.

Those features almost always change once users show up.

MVPs Help Validate Assumptions Early (Before They Become Expensive Lies)

Every startup is built on assumptions:

- Who the user is

- What problem actually matters

- How often the problem occurs

- What users are willing to change to solve it

The danger is not having assumptions. The danger is not knowing which assumptions are false.

An MVP turns assumptions into testable hypotheses.

Instead of asking users what they would do, you observe what they actually do. This aligns closely with the Build–Measure–Learn loop popularized by Eric Ries, where learning velocity matters more than output volume.

I’ve seen founders completely change positioning, pricing, and even target customers after MVP feedback. Those pivots were not failures. They were corrections made while there was still room to maneuver.

MVPs Enable Faster Go-to-Market (Speed With Purpose)

Speed alone is meaningless if you’re running in the wrong direction. But validated speed is a competitive advantage.

An MVP gets you in front of users faster, which means:

- Earlier feedback

- Early traction signals

- Earlier conversations with customers

- Earlier credibility with investors and partners

Some of the most successful startups didn’t win because they built the best product first. They won because they learned faster.

We bias heavily toward launching early and learning in public, even if that means the product feels uncomfortable at first. Founders who embrace this tend to make sharper decisions later, because those decisions are grounded in reality, not assumptions.

An MVP isn’t about rushing. It’s about respecting time. Yours, your team’s, and your users’.

Key Characteristics of an MVP

Over the years, I’ve noticed that founders rarely fail at building things. They fail at building the right thing at the right time. That’s where understanding the core characteristics of an MVP really matters.

An MVP isn’t defined by how small it is. It’s defined by how focused it is.

Here are the traits I look for when evaluating whether something is truly an MVP or just a scaled-down product pretending to be one.

It Solves One Core Problem, Clearly

A real MVP is opinionated. It takes a stand on what problem matters most.

If your product tries to solve multiple problems at once, it’s not an MVP. It’s a compromise. And compromises are hard to validate.

When we work with founders at StartupGuru and NCrypted, one of the first exercises we do is brutally simple:

“If this product could only do one thing well, what would it be?”

Most founders hesitate here. That hesitation is the signal.

Great MVPs are narrow by design. They don’t try to impress everyone. They try to resonate deeply with a very specific user facing a very specific pain.

It Is Built for Learning, Not Perfection

This is where engineering instincts often clash with startup reality.

An MVP is not built to be perfect, scalable, or future-proof. It’s built to answer questions.

Questions like:

- Do users understand the value without explanation?

- Where do they get stuck?

- What do they ignore completely?

- What do they ask for unprompted?

At StartupGuru, we actively discourage founders from polishing MVPs too early. Pixel perfection and edge-case handling can wait. What cannot wait is feedback.

If your MVP doesn’t surprise you in some way once users start using it, you probably already overbuilt it.

It Has Just Enough Features to Be Usable

This is the hardest balance to strike.

Too few features, and users can’t experience the value.

Too many features, and you don’t know what actually mattered.

A strong MVP sits in the uncomfortable middle. It feels incomplete to the builder, but useful to the user.

One internal rule we follow is this:

If a feature does not directly support the core use case, it does not belong in the MVP.

That discipline saves months of unnecessary development and prevents founders from falling in love with features instead of outcomes.

It Is Designed for Early Adopters, Not Everyone

MVPs are not meant for mass adoption. They are meant for early adopters who are willing to tolerate rough edges in exchange for solving a real problem.

If your MVP requires mainstream users to succeed, the bar is already too high.

Early adopters:

- Forgive imperfections

- Give honest feedback

- Help shape the product direction

At StartupGuru, we often help founders identify who these early users actually are, because they’re rarely the same audience targeted in pitch decks.

We call them passionate users, who are as passionate about the problem you’re trying to solve as you are as a founder.

Therefore, designing for these early adopters changes everything, from UX decisions to onboarding to support expectations.

It Creates Measurable Signals, Not Vanity Metrics

Finally, a real MVP produces signals you can act on.

Not downloads.

Not signups alone.

And not polite compliments.

Meaningful signals look like:

- Repeated usage

- Time spent on the core action

- Willingness to pay or commit time

- Referrals without incentives

If your MVP can’t tell you what to do next, it’s not doing its job.

An MVP should reduce ambiguity. Even bad results are good outcomes if they help you make a clearer decision.

And that’s how we evaluate MVPs at StartupGuru. Not by how impressive they look, but by how much clarity they create for the founder.

So, this mindset becomes even more important when founders confuse MVPs with prototypes or proof of concept. And that confusion is more common than you’d think.

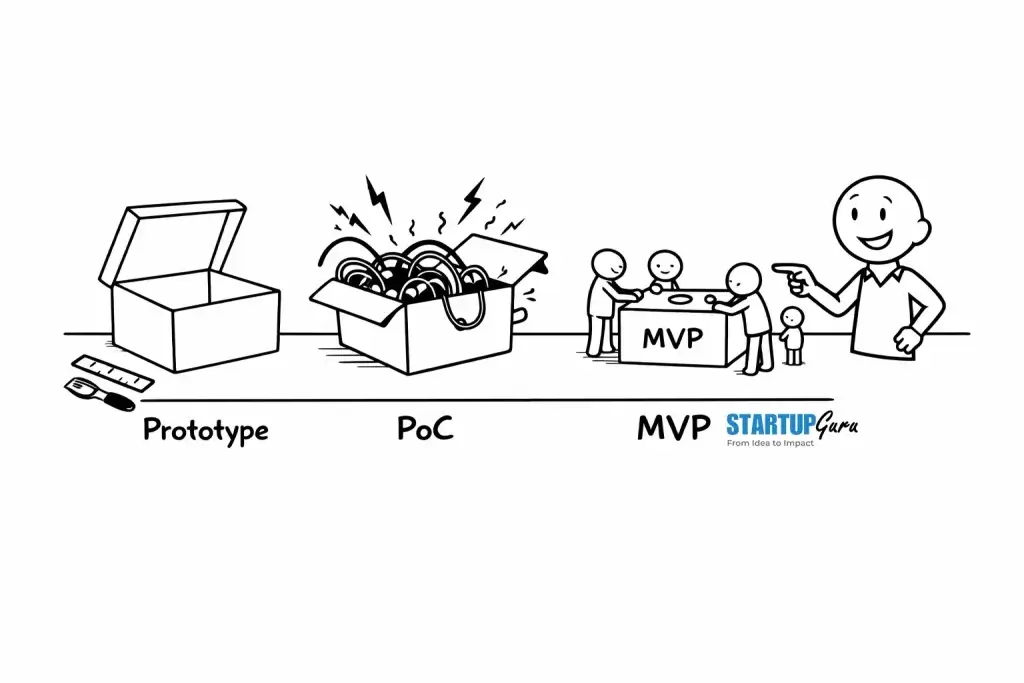

MVP vs Prototype vs Proof of Concept (PoC)

This is one of those sections where I’ve seen even experienced founders get tangled up. And honestly, it’s not their fault. The startup ecosystem throws these terms around interchangeably, even though they serve very different purposes.

You need to be very deliberate about this distinction because choosing the wrong approach at the wrong stage can cost you months.

Let’s break this down in plain terms.

Prototype: Does This Make Sense to a User?

A prototype is about clarity, not validation.

It helps answer questions like:

- Do users understand the flow?

- Does the idea make intuitive sense?

- Is the experience confusing or obvious?

Prototypes are often:

- Clickable Figma designs

- Wireframes

- Mock screens with limited or no backend

They are excellent for early conversations, especially when the idea is still abstract. But here’s the catch: prototypes collect opinions, not behavior.

Users will tell you what they think they would do. That’s useful, but it’s not the truth.

Our founders use prototypes sparingly and with intent. They are a tool for alignment and early feedback, not decision-making. If founders stay in prototype mode for too long, they start optimizing for approval instead of reality.

Proof of Concept (PoC): Can This Be Built at All?

A Proof of Concept answers a very specific question:

Is this technically feasible?

PoCs are common in:

- Deep tech

- AI/ML-heavy products

- Hardware or infrastructure startups

- Regulated industries

A PoC might prove that:

- A model can achieve acceptable accuracy

- A system can scale to a certain load

- An integration is even possible

What a PoC does not prove is demand.

And this is where founders sometimes fool themselves. A successful PoC feels like progress, but it doesn’t mean users want the product. It only means the product can exist.

We’ve seen founders at StartupGuru invest heavily in PoCs and delay market exposure. When they finally speak to users, the problem itself turns out to be misdefined. That’s an expensive lesson.

MVP: Will People Actually Use This?

An MVP sits at the intersection of desirability and feasibility.

It answers questions like:

- Will users change their behavior for this?

- Will they come back after the first use?

- Will they pay, commit time, or recommend it?

Unlike prototypes or PoCs, an MVP:

- Is used by real users

- Exists in the real world

- Produces measurable behavior

This distinction matters because each tool optimizes for a different outcome.

A simple way I explain this to founders is:

- Prototype = understanding

- PoC = confidence

- MVP = evidence

Avoid jumping straight into MVPs when clarity or feasibility is missing. But I would also advise against hiding behind prototypes and PoCs when the real risk is market demand.

The Costly Mistake Founders Make

The most common mistake I see is founders treating a prototype or PoC as a substitute for an MVP.

They’ll say:

- “Users liked the design.”

- “The tech works.”

- “Investors were impressed.”

None of those validate the demand.

An MVP forces accountability. It doesn’t care how elegant your architecture is or how polished your UI looks. It only cares whether users show up and stick around.

And choosing between a prototype, PoC, and MVP isn’t about preference. It’s about asking the right question at the right time.

And once that’s clear, the next challenge founders face is deciding what kind of MVP actually makes sense for their situation.

At StartupGuru and our incubation program, we ask our founders to think beyond even MVPs. While MVP answers “will people use this product?”, our founders go for the MSP model (Minimum Sellable Product), which answers “are people paying for this?”. Note, we answer “are they paying”, not “if they will pay”, that makes the whole difference.

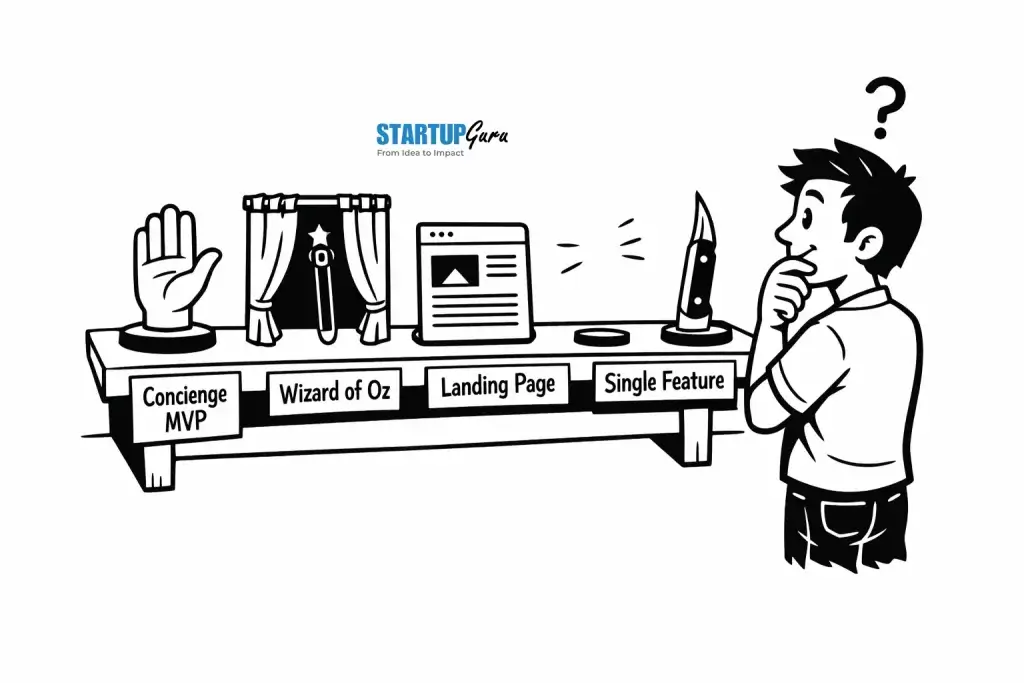

Types of MVPs

One of the biggest mistakes I see founders make is assuming there’s only one “correct” way to build an MVP. Usually, that means jumping straight into building software.

Well, that’s not always the smartest move.

An MVP is a strategy, not a format. The right MVP depends on what you’re trying to validate first. At StartupGuru, we choose the MVP type based on where the highest uncertainty lies, not on what feels most impressive.

Here are the MVP types we see work consistently well.

Concierge MVP

A Concierge MVP delivers the value manually before automating anything.

Instead of building systems, you act as the system.

This works especially well when:

- The problem is complex

- The solution requires high trust

- You need deep user insight early

A classic example is early Airbnb. Before automation, the founders personally helped hosts take photos, list properties, and manage bookings. That manual effort helped them understand what actually mattered to users.

As you can guess now, we often recommend concierge MVPs to B2B founders we work with. Yes, it doesn’t scale. That’s the point. It helps you learn before scaling the wrong thing.

Wizard of Oz MVP

In a Wizard of Oz MVP, the product appears automated to the user, but behind the scenes, humans are doing the work.

From the user’s perspective, it feels like software. Internally, it’s scrappy and manual.

This approach is powerful when:

- Automation is expensive or risky

- You want to validate workflows before building them

- Speed matters more than efficiency

Zappos famously used this approach early on by listing shoes online and buying them manually from stores after customers placed orders.

At StartupGuru, we like Wizard of Oz MVPs when founders want to test user behavior without committing to heavy engineering upfront.

Landing Page MVP

A landing page MVP is often misunderstood. It’s not just a marketing page. It’s a demand test.

The goal is to see whether users:

- Sign up

- Join a waitlist

- Click a call-to-action

- Show intent without a product behind it

This is particularly useful in the very early stages, when you’re still validating positioning and messaging.

Dropbox’s early explainer video falls into this category. It communicated value clearly and measured interest before product maturity.

So, we’ve used landing page MVPs at StartupGuru to help founders kill bad ideas early. And that’s a win, even if it doesn’t feel like one at the time.

Single-Feature MVP

A single-feature MVP focuses on doing one thing exceptionally well.

Instead of building a platform, you build a sharp tool.

This works best when:

- One feature delivers disproportionate value

- The problem is narrow but painful

- Usage frequency matters

If you are old enough to remember, early Instagram is a good example. It wasn’t a social network. It was a photo-sharing app with filters. Everything else came later.

We push founders toward single-feature MVPs when they’re tempted to build “platforms” too early. Platforms without usage are just ideas with dashboards.

No-Code or Low-Code MVP

Today, no-code tools have changed the MVP game entirely.

Founders can validate ideas using tools like Webflow, Bubble, or Airtable before writing serious code.

This approach is effective when:

- Speed matters more than customization

- The idea is still fluid

- You want to test workflows, not architecture

We regularly encourage non-technical founders to start here. Not because no-code is the end goal, but because it shortens the distance between idea and feedback.

Choosing the Right MVP Type

There is no universally “best” MVP type.

The right question is:

What is the riskiest assumption in this business right now?

At StartupGuru, we design MVPs to attack that assumption first. Sometimes that means code. Often, it doesn’t.

Once founders pick the right MVP type, the next challenge is execution. Knowing how to actually build and launch an MVP without drifting into full-product mode is where most teams struggle.

MVP Development Process (How We Actually Do It)

This is the part founders usually expect to be complex. In reality, the MVP development process is simple. What makes it hard is discipline.

Most teams don’t fail because they don’t know the steps. They fail because they skip steps, rush decisions, or quietly expand scope while telling themselves it’s still an MVP.

At StartupGuru, we follow a process that’s intentionally boring. Boring is good. It keeps emotions out of decisions.

1: Start With the Problem, Not the Idea

Every MVP should start with a problem statement, not a solution.

Yet founders almost always walk in with a solution-first mindset. That’s normal. It’s also risky.

So we force clarity early:

- Who is the user?

- What specific problem are they facing?

- How are they solving it today?

- Why is that solution inadequate?

If these answers are fuzzy, building an MVP is premature.

And one thing we actively avoid at StartupGuru is turning vague frustrations into products. “People struggle with X” is not enough. We push until the pain is concrete, frequent, and costly in some way.

2: Define the Core Use Case

Once the problem is clear, we narrow the scope aggressively.

An MVP should revolve around one core action. One moment where value is delivered.

Examples:

- Sending the first invoice

- Booking the first appointment

- Completing the first task

- Getting the first insight

Everything else is secondary.

If you can’t describe your MVP’s core use case in one sentence, the scope is already too wide.

This is where many founders push back. They worry the product will look too thin. In practice, thin products are easier to understand, easier to test, and easier to fix.

3: Ruthless Feature Prioritization

This is where theory meets resistance.

Founders often say, “But users will expect this,” or “We’ll need this later anyway.”

Maybe. But later is not now.

At StartupGuru, we prioritize features using a simple filter:

Does this feature directly support the core use case?

If the answer isn’t a clear yes, it doesn’t make it into the MVP.

This approach aligns closely with lean product principles, where reducing waste is as important as building value.

4: Build Fast, But Intentionally

Speed matters, but direction matters more.

We optimize MVP builds for:

- Short development cycles

- Easy changes

- Low emotional attachment to code

This is why we often choose simpler stacks, temporary workarounds, or even manual processes early on. The goal is not elegance. The goal is learning velocity.

Founders who have worked with us at StartupGuru will know this upfront:

Expect parts of the MVP to be thrown away. If that idea makes you uncomfortable, you’re probably overbuilding.

5: Launch to Real Users Early

An MVP that isn’t launched is just a project, no better than your napkin-sketch concept.

We encourage founders to get the MVP in front of real users as soon as the core flow works, even if:

- Onboarding is clunky

- UI feels rough

- Features are missing

Early users don’t expect perfection. They expect usefulness.

What matters is observing behavior:

- Do users complete the core action?

- Do they come back?

- Do they ask for specific improvements?

This is where assumptions start collapsing. And that’s a good thing.

6: Measure What Actually Matters

Metrics can mislead if you’re not careful.

For MVPs, we focus on signals that indicate real value:

- Repeated usage

- Time spent on the core action

- Willingness to pay, wait, or switch

- Organic referrals or invites

Vanity metrics are tempting. We actively avoid optimizing for them early because they create false confidence.

7: Decide What to Do Next

An MVP always leads to a decision.

That decision is usually one of three:

- Double down

- Pivot

- Stop

None of these outcomes is a failure.

At StartupGuru, we consider an MVP successful if it leads to clarity, even if that clarity is uncomfortable. Founders who make decisive moves at this stage save themselves years of slow, unfocused execution.

And once you’ve gone through this process, there’s another important question founders often ask themselves: when does an MVP actually stop being an MVP, and when does it turn into something more?

MVP Success Stories (What Worked and Why)

Founders often ask me for frameworks. What they really want are patterns. Patterns show up most clearly when you look at real examples, especially the early, messy versions that don’t make it into polished case studies.

Here are a few MVP examples I reference often, not because they’re famous, but because they demonstrate the thinking behind a good MVP.

Dropbox: Validating Demand Before Building

How Dropbox started is probably the most cited MVP example, and for good reason. But the important detail is often missed.

Their first MVP wasn’t the product. It was a short explainer video that demonstrated how the product would work. That video resonated deeply with a very specific audience that already felt the pain of file syncing across devices.

The result was a massive spike in signups overnight, without a scalable product in place.

The lesson here isn’t “make a video.” It’s this:

Validate demand before committing to heavy engineering.

At StartupGuru, we’ve used similar approaches when the cost of building first is high, and the uncertainty around demand is even higher.

Airbnb: Manual Before Automated

Early Airbnb didn’t look like a global marketplace. It looked like a scrappy website with founders deeply involved in every transaction.

They manually onboarded hosts, helped them create listings, and even took photos themselves. None of this was scaled, but all of it created insight.

The MVP worked because it focused on one core problem: helping people monetize unused space and helping travelers find affordable places to stay.

This is a textbook example of a concierge MVP. The founders learned what made listings convert, what guests cared about, and where trust broke down.

We encourage founders at StartupGuru to embrace this phase instead of rushing past it. Manual effort early is often the fastest path to clarity.

Deep dive: Airbnb business model

Uber: Narrow Scope, Real Usage

Uber didn’t launch as a global platform. It launched as a simple app to book black cars in San Francisco.

No surge pricing. No ride categories. No multi-city expansion.

The MVP validated a single behavior: would people tap a button to get a car instead of calling one?

Once that behavior was proven, everything else followed.

The takeaway here is focus. Uber didn’t try to solve transportation everywhere. It solved a very specific use case extremely well.

This is something we constantly remind founders at StartupGuru. Scope is not your enemy. Diffusion is.

Buffer: Testing Willingness to Pay

Buffer’s MVP started with a landing page that explained the product. When users clicked “Sign up,” they were shown pricing plans. Only after they selected a plan were they told the product wasn’t ready yet.

That flow tested two critical assumptions:

- Did users want this?

- Were they willing to pay?

Only after validating both did the team build the product.

This is an approach we recommend when pricing is a major unknown. It’s far better to learn early that users won’t pay than to discover it after months of development.

What These Examples Have in Common

These MVPs look very different on the surface, but they share a few underlying traits:

- They validated the riskiest assumption first

- They avoided premature scaling

- They prioritized learning over polish

At StartupGuru, we don’t copy MVPs. We copy principles. The format always changes. The thinking shouldn’t.

And once founders see what good MVPs look like in the real world, the next question usually comes naturally: are there situations where building an MVP is actually the wrong move?

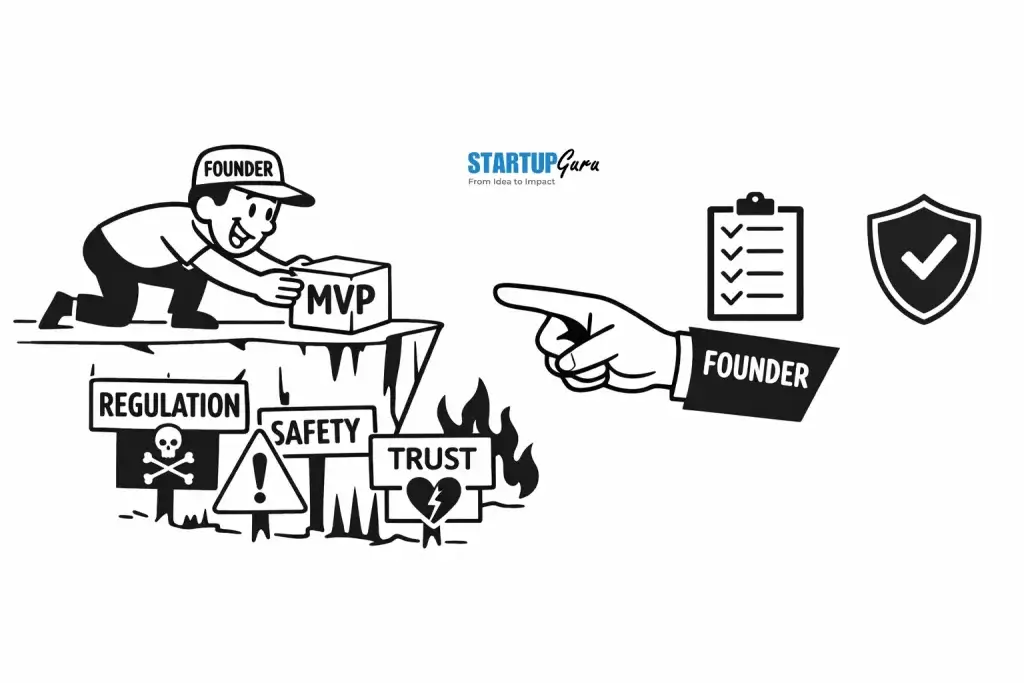

When an MVP Is Not the Right Choice for Your Startup

As much as I believe in MVPs, I’m also very clear about this: not every startup should rush into building one.

This is where nuance matters. Blindly applying the MVP playbook can be just as dangerous as ignoring it altogether. At StartupGuru, we’ve advised founders not to build an MVP in certain situations, even when they were eager to move fast.

Here’s when pressing pause is the smarter move.

When the Risk Is Technical, Not Market-Based

MVPs are excellent for validating demand. They are not always the best tool for validating deep technical feasibility.

If your startup depends on:

- Novel algorithms

- Hard scientific breakthroughs

- Complex infrastructure

- Hardware integration

Then the biggest unknown may not be “Will users want this?” but “Can this even work at a basic level?”

In these cases, a proof of concept often needs to come before an MVP. Otherwise, you risk validating demand for something that isn’t realistically buildable.

At StartupGuru, we see this frequently in AI-heavy products. Founders want to ship fast, but if the core system cannot meet a minimum accuracy or latency threshold, user feedback becomes meaningless.

When You’re Operating in Highly Regulated Industries

Some industries simply don’t tolerate rough edges.

If you’re building in:

- Healthcare

- Fintech

- Insurance

- Legal or compliance-heavy domains

Shipping an incomplete or loosely validated product can do real damage. Not just to your startup, but to users.

In these cases, the MVP still exists, but it looks very different. It might be:

- A tightly controlled pilot

- A closed beta with compliance guardrails

- A manually operated service with limited exposure

What we avoid at StartupGuru is pushing founders to “just launch” in environments where trust and safety are non-negotiable. Speed matters, but responsibility matters more.

When Trust Is the Product

Some products live or die on trust from day one.

Think about:

- Security tools

- Financial products

- Infrastructure services

- B2B systems that touch critical workflows

Here, a visibly rough MVP can work against you. Early users may not forgive failures, even if they understand the product is new.

In these situations, we often advise founders to validate workflows, pricing, and demand through manual services, pilots, or partnerships before exposing users to software.

The MVP still exists, but it’s often invisible to the end customer.

When Founders Use MVPs to Avoid Hard Thinking

This is the uncomfortable one.

Sometimes, founders want to build an MVP because it feels like progress. It gives the illusion of momentum.

But if:

- The problem isn’t clearly defined

- The target user keeps changing

- The value proposition can’t be explained simply

Then an MVP won’t fix that confusion. It will amplify it.

At StartupGuru, we slow founders down deliberately in these moments. Building something is not always the answer. Clarity usually is.

The Real Question to Ask

Instead of asking, “Should we build an MVP?” I encourage founders to ask:

What is the biggest unknown in this business right now?

If that unknown is about user behavior, demand, or willingness to pay, an MVP is usually the right move.

If it’s about feasibility, safety, or trust, something else may need to come first.

Understanding this distinction saves founders from using MVPs as a reflex instead of a strategy.

And once that clarity is in place, the final challenge is knowing how to judge whether an MVP is actually successful, beyond surface-level metrics.

How to Measure MVP Success (What Actually Matters)

This is where many MVP efforts quietly fail.

Founders build something, launch it, get a mix of reactions, and then don’t know what to do next. The problem isn’t a lack of data. It’s looking at the wrong signals.

An MVP is not successful because it exists. It’s successful if it reduces uncertainty and helps you make a clearer decision.

At StartupGuru, we judge MVP success by one question:

Do we know what to do next with more confidence than before?

Behavior Beats Feedback Every Time

The most common mistake founders make is over-weighting opinions.

Users will say:

- “This is interesting.”

- “I’d use this.”

- “Nice idea.”

None of that means anything unless behavior supports it.

What matters more:

- Do users complete the core action?

- Do they come back without reminders?

- Do they change how they currently work?

At StartupGuru, we tell founders to watch what users do when no one is guiding them. That’s where truth shows up.

Focus on One or Two Core Metrics

Early-stage products don’t need dashboards full of numbers.

In fact, too many metrics usually mean no clarity.

For an MVP, we narrow measurement down to:

- One primary success metric tied to the core use case

- One supporting metric that shows momentum or decay

Examples:

- A scheduling MVP might focus on completed bookings

- A B2B tool might focus on weekly active usage per account

- A marketplace MVP might focus on successful matches

We actively avoid vanity metrics like raw signups or page views unless they directly connect to real usage.

Retention Tells You More Than Acquisition

Anyone can get attention. Retention is harder.

If users don’t come back, it usually means:

- The problem isn’t painful enough

- The solution doesn’t deliver real value

- The experience is too confusing

At StartupGuru, we pay close attention to what happens after first use. A small group of users who keep coming back is far more valuable than a large group that disappears.

This thinking aligns closely with how experienced investors look at early traction. Retention is often a stronger signal than growth in the early days.

Willingness to Pay or Commit Is a Strong Signal

Money is not the only form of commitment, but it’s an honest one.

If users:

- Pay, even a small amount

- Prepay or join a waitlist

- Invest time setting things up

- Bring others without incentives

Those are strong indicators that you’re solving something real.

At StartupGuru, we encourage founders to test pricing earlier than they’re comfortable with. Delaying pricing delays truth.

Clear Outcomes Matter More Than Good News

A successful MVP doesn’t always deliver positive results.

Sometimes, the best outcome is realizing:

- The problem isn’t big enough

- The user isn’t who you thought

- The solution needs to change fundamentally

That’s not failure. That’s progress.

At StartupGuru, we consider an MVP successful if it leads to a decisive action:

- Double down

- Pivot

- Walk away

Indecision is the real enemy.

What We Avoid Measuring Too Early

There are things we intentionally ignore during the MVP stage:

- Scalability metrics

- Performance benchmarks

- Long-term retention curves

- Polished conversion funnels

Those matters later. Measuring them too early creates pressure to optimize something that hasn’t earned the right to exist yet.

An MVP is a compass, not a scorecard. Its job is to point you in the right direction, not to impress anyone.

And if you’ve made it this far, you’re already ahead of most founders. The hard part isn’t understanding MVPs. It’s having the discipline to use them honestly.

Frequently Asked Questions About MVPs

Below are the questions I hear most often from founders when they’re either about to start building or are already halfway into an MVP and feeling unsure.

I’ll answer these the same way I do in real conversations at StartupGuru. Directly, without theory for the sake of theory.

How small is too small for an MVP?

If users cannot experience the core value, it’s too small.

An MVP should feel uncomfortable to you, not useless to the user. If someone can complete the main action and understand why the product exists, you’re usually in the right zone.

What we avoid at StartupGuru is building MVPs that are technically impressive but emotionally empty. If users don’t feel relief, speed, clarity, or progress after using it, size doesn’t matter.

Should an MVP be built only for early adopters?

Yes. And this is non-negotiable.

If your MVP requires mainstream users to succeed, you’re setting the bar unrealistically high. Early adopters tolerate rough edges because the problem hurts enough.

At StartupGuru, we design MVPs assuming users will forgive imperfections but not confusion. If early adopters don’t care, mainstream users never will.

How long should MVP development take?

There’s no universal number, but here’s a practical rule of thumb.

If it takes more than a few weeks to get in front of real users, you’re probably overbuilding.

Timeframes stretch when founders:

- Keep adding “just one more feature”

- Delay launch for polish

- Try to future-proof the product

At StartupGuru, we bias toward shorter cycles because learning decays when momentum slows.

Can an MVP be no-code or manual?

Absolutely. And often, it should be.

Some of the best MVPs never start as software. Manual workflows, spreadsheets, landing pages, and concierge-style services all count if they validate the right assumption.

We regularly encourage founders to delay custom development until behavior justifies it. Code is a liability until it earns its place.

Do investors expect a polished MVP?

Good investors don’t expect a goody-goody MVP. Often, what looks good doesn’t necessarily sell. They expect clarity.

They care more about:

- What you learned

- How users behaved

- What changed as a result

- How quickly you adapted

At StartupGuru, we’ve seen founders raise capital with rough MVPs because they could clearly explain traction, insight, and direction. Polish impresses demos. Learning impresses investors.

Should I include pricing in my MVP?

If pricing is a critical part of the business, then yes, as early as possible.

You don’t need perfect pricing. You need signals.

Testing willingness to pay, even informally, saves founders from building products people like but won’t buy. We almost always push founders to test pricing earlier than they expect.

When does an MVP stop being an MVP?

An MVP stops being an MVP when:

- You’ve validated the core problem

- You understand user behavior

- You’re confident about the direction

At that point, the conversation shifts from validation to scaling and optimization.

What we avoid is staying in “permanent MVP mode.” That’s usually a sign of fear, not strategy.

What’s the biggest MVP mistake founders make?

Treating the MVP as a deliverable instead of a learning system.

Founders often ask, “Is the MVP done?”

The better question is, “What did we learn, and what are we changing because of it?”

If nothing changes, the MVP didn’t do its job.

If you’re building an MVP right now and something feels heavier than it should, that’s usually a signal worth listening to. MVPs are meant to create clarity, not complexity.

Take away

If there’s one thing I want you to take away from all of this, it’s this: an MVP is not about building less. It’s about learning faster with intent.

Most startups don’t die because they lack ambition. They die because they committed too early to assumptions that were never tested properly. An MVP is your chance to stay honest with yourself while there’s still room to change direction.

At StartupGuru, we don’t treat MVPs as a checkbox or a phase you rush through. We treat them as a discipline. A way to replace opinions with evidence, and excitement with clarity. When done right, an MVP doesn’t just shape the product. It shapes how you think as a founder.

If you’re willing to stay uncomfortable, cut ruthlessly, and listen to what users actually do, not what they say, the MVP will do its job. And if it tells you something you didn’t want to hear, that’s usually the most valuable outcome you could hope for.