Most startup ideas do not start with code.

They start with a frustration, a pattern someone noticed at work, or a gap in the market that feels obvious once you see it.

And yet, the moment you decide to turn that idea into a product, everything suddenly feels technical.

APIs. Tech stacks. Databases. Frameworks. MVP scope.

If you are a non-technical founder, this is usually the point where confidence drops, and hesitation creeps in.

You might start asking questions like:

- Do I need a technical co-founder?

- Can I even build an MVP if I do not understand development?

- How do I know if I am making the right technical decisions?

At StartupGuru, we’ve worked with founders who came from sales, operations, consulting, healthcare, and even manufacturing. Very few of them started with technical confidence, but many built strong MVPs once the process was clarified.

This article exists for that exact moment.

Not to teach you how to code.

Not to push you toward hiring anyone.

But to help you understand how MVP development actually works when you are a non-technical founder, and how to approach it without losing control of your product, your money, or your direction.

In the majority of the startups we have worked with, the founders who succeeded were not the most technical, but the ones who stayed closest to the problem they were solving.

In this post, we'll cover:

- 1 Why Non-Technical Founders Struggle With MVP Development

- 2 What an MVP Really Means for a Non-Technical Founder

- 3 Do You Really Need a Technical Co-Founder?

- 4 Common MVP Mistakes Non-Technical Founders Make

- 5 How Non-Technical Founders Should Approach MVP Development

- 6 Different Ways to Build an MVP Without a CTO

- 7 What Non-Technical Founders Should Look for in a Tech Partner

- 8 What Happens After the MVP Is Built

- 9 FAQs: MVP Development for Non-Technical Founders

- 9.1 Do I need to learn coding to build an MVP?+

- 9.2 How long does it usually take to build an MVP?+

- 9.3 How much should a non-technical founder budget for an MVP?+

- 9.4 What is the difference between an MVP and a prototype?+

- 9.5 Can I use no-code or low-code tools to build my MVP?+

- 9.6 How do I know if my MVP scope is too big?+

- 9.7 What should I track once the MVP is live?+

- 9.8 When should I consider hiring a technical co-founder?+

- 9.9 Is it a failure if my MVP does not work?+

- 9.10 What matters most for a non-technical founder during MVP development?+

Why Non-Technical Founders Struggle With MVP Development

The problem is not intelligence.

And it is not effort.

Most non-technical founders struggle with MVP development because product decisions are often framed as technical decisions, even when they are not.

In our work at StartupGuru, we’ve seen founders slowly lose ownership of their product simply because every discussion started sounding technical. Over time, they stopped asking why and focused only on delivery.

An MVP is supposed to answer business questions:

- Will users care?

- Will they come back?

- Does this solve a real problem?

- Is there a path to product-market fit?

But what founders are usually pulled into instead is:

- Feature lists

- Technical feasibility debates

- Development timelines

- Tool and framework discussions

This creates an immediate imbalance.

A common pattern we’ve observed is founders approving features they did not fully understand, just to keep momentum going. That decision usually shows up later as rework or wasted spend.

When you do not speak the language of development, it becomes very easy to:

- Defer decisions to developers

- Assume complexity equals quality

- Confuse progress with output

This is how many MVPs quietly fail.

Research from CB Insights consistently shows that one of the top reasons startups fail is building something the market does not need. Not bad code. Not poor technology. Wrong priorities.

For non-technical founders, this risk is higher because:

- Validation is skipped in favor of building

- Features are added instead of clarified

- Decisions feel irreversible when they are not

There is also a psychological layer to this.

When you don’t understand the technical side, it is tempting to believe that someone else should “own” the product once development starts. That mindset slowly disconnects the founder from the product itself.

An MVP does not fail because a founder cannot code.

It fails when the founder loses clarity over what the product is trying to learn.

We will discuss about how to prevent that.

Now, we need to reset what an MVP actually means when you are not coming from an engineering background, because most confusion starts there.

What an MVP Really Means for a Non-Technical Founder

For non-technical founders, the term MVP often gets interpreted the wrong way.

It is commonly understood as:

- a smaller version of the final product

- a cheaper first build

- a quick launch to “get something out there”

None of these are wrong on the surface. But they miss the core purpose.

An MVP is not defined by how little you build.

It is defined by what you are trying to learn.

Some of the most successful MVPs we’ve seen at StartupGuru were surprisingly simple. In a few cases, founders validated demand with just one core flow, while competitors were still building dashboards.

Eric Ries, in his concept of the Lean Startup Methodology, originally framed the MVP as a way to validate assumptions with the least amount of effort and time, not as a stripped-down product version. That distinction matters a lot if you do not come from an engineering background.

When you are non-technical, it is easy to equate effort with value. More screens feel safer. More features feel complete. More development time feels like progress.

But learning does not scale linearly with features.

In fact, studies and postmortems of failed startups show the opposite. Teams that build too much too early often delay feedback, increase sunk cost, and make it harder to pivot later. CB Insights lists “no market need” as the number one reason startups fail, and this is often discovered too late because validation was postponed in favor of building.

From a non-technical perspective, an MVP should be thought of as:

- a controlled experiment

- a test of a specific user behavior

- a way to validate a value proposition, not an idea in general

This is where many founders get misled by development conversations.

A developer might ask, “Should we include this feature now or later?”

The better question for a founder is, “What decision will this feature help us make?”

If a feature does not help you confirm or reject an assumption about users, pricing, or usage, it probably does not belong in the MVP.

Another common misunderstanding is treating MVP quality as a technical standard.

Non-technical founders sometimes worry that an MVP must look unfinished or unreliable. That is not the goal either. An MVP should be functionally credible, even if it is narrow in scope.

Users forgive missing features more easily than confusing flows or broken experiences. Research on early user adoption consistently shows that clarity of purpose matters more than feature breadth, especially in early-stage products.

We’ve also seen the opposite. Founders who built visually impressive MVPs but struggled to explain what assumption the product was actually testing.

So for a non-technical founder, the real shift is this:

Your job is not to define how the product is built.

Your job is to define what needs to be proven before you invest more.

Once that mindset is in place, MVP development stops feeling like a technical black box and starts becoming a structured decision-making process.

Do You Really Need a Technical Co-Founder?

This is one of the first questions non-technical founders ask us. And usually, it comes from pressure rather than clarity.

You hear stories about startups where the technical co-founder “built everything from scratch” or where investors insist that a strong engineering presence is mandatory from day one. Over time, this creates the belief that without a CTO, progress is impossible.

That belief is incomplete.

A technical co-founder makes sense when technology itself is the core differentiator. Deep infrastructure, proprietary algorithms, complex data systems, or highly specialized engineering problems often justify long-term technical ownership at the founder level.

But many startups do not start there.

In the early stages, most risk is not technical. It is product risk and market risk.

Will users care?

Would they behave the way you expect?

Will they pay?

Will the problem stay painful enough?

We’ve worked with founders who rushed into technical co-founder relationships and later found it difficult to change direction once validation contradicted early assumptions.

Several founder surveys and accelerator retrospectives show that premature co-founder decisions are a common regret. Founders often give away significant equity before they understand the real technical needs of the business. Y Combinator has repeatedly pointed out that founder breakups and misaligned co-founder roles are a major cause of early startup failure, especially when equity is split before validation.

For a non-technical founder, the real danger is not lacking a CTO. It is locking yourself into a long-term technical relationship before you understand what you are building.

In contrast, we have seen that the founders who delayed this decision often made more informed choices once they understood the real technical complexity of their product.

There are also practical issues that rarely get discussed openly.

A technical co-founder is not just someone who can write code. They are expected to:

- make architectural decisions that affect scalability

- hire and manage engineers later

- balance speed with long-term maintainability

In the MVP phase, many of these responsibilities are either premature or based on assumptions that will change once real users interact with the product.

This is why many successful founders delay the decision.

They use the MVP phase to:

- validate the problem and solution

- understand technical complexity through execution

- learn what kind of technical leadership they actually need

Only after that does the question of a technical co-founder become clearer.

There are other models that reduce risk early on. Fractional CTOs, technical advisors, and product-led development partners exist specifically to help non-technical founders navigate MVP development without making irreversible equity decisions. These approaches allow founders to stay close to product decisions while keeping flexibility.

The key point is not that a technical co-founder is unnecessary.

It is that the timing of that decision matters far more than most founders realize.

For non-technical founders, MVP development should be a phase of learning and clarity, not commitment and lock-in.

Common MVP Mistakes Non-Technical Founders Make

Many founders come to us after spending months on features that users barely touched, not because the idea was bad, but because prioritization was never grounded in validation.

Most MVP mistakes made by non-technical founders are not obvious at the time they are made. They feel reasonable. Often, they are even encouraged.

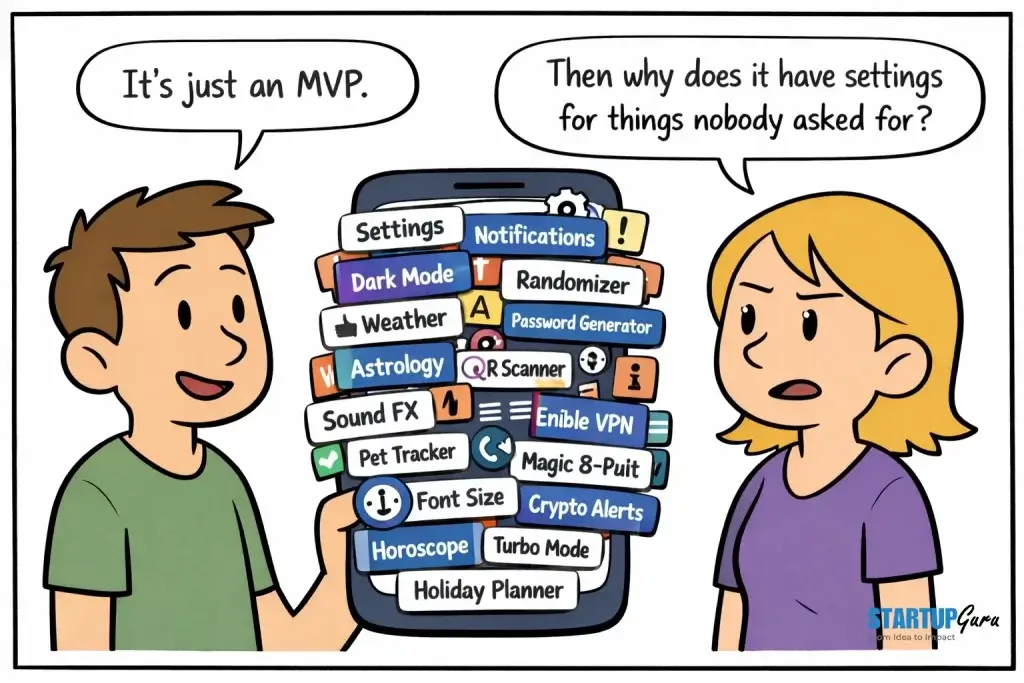

One of the most common mistakes is starting with features instead of problems.

A founder explains the idea, the conversation quickly turns into a list of screens, buttons, and workflows, and the MVP slowly becomes a checklist. What gets lost is the original question the product was supposed to answer. Features become proxies for progress, even though no learning has happened yet.

Another frequent issue is letting development define the product.

When you are not technical, it can feel logical to step back and let developers decide what should be built. The intention is good. The outcome often is not. Developers are trained to solve technical problems efficiently. They are not responsible for validating market assumptions unless explicitly asked to do so. When product direction is delegated entirely, the MVP often reflects technical convenience rather than user reality.

There is also a tendency to confuse complexity with seriousness.

Many non-technical founders believe that a “real” MVP needs advanced functionality, integrations, or scalability from day one. This usually comes from fear. Fear that users will not take the product seriously. Fear that investors will dismiss it. Fear that rebuilding later will be costly.

In practice, early users respond to usefulness, not sophistication. Multiple studies on early product adoption show that users are willing to tolerate missing features if the core value is clear and the experience is coherent. What they do not tolerate well is confusion.

Poor prioritization is another quiet failure point.

Without clear validation goals, everything feels equally important. Edge cases get implemented early. Rare scenarios receive as much attention as core flows. Budgets stretch, timelines slip, and the MVP slowly turns into a partial full product, without the learning that justifies it.

Then there is the assumption that technical decisions are irreversible.

This belief leads founders to overthink architecture and future scale before the present problem is understood. In reality, most early technical decisions are reversible at far lower cost than building the wrong product entirely. The expensive mistake is not rewriting code. It is investing months into validating the wrong thing.

Finally, many non-technical founders treat the MVP as a deliverable rather than a process.

The MVP is launched, feedback is collected informally, and development continues without structured learning. No clear metrics. No defined success criteria. No decision points. At that stage, even valuable feedback struggles to influence direction.

None of these mistakes come from incompetence.

They come from a lack of clarity about what the MVP phase is supposed to protect you from.

One recurring issue we see is founders realizing too late that they paid to build certainty, when they actually needed learning.

How Non-Technical Founders Should Approach MVP Development

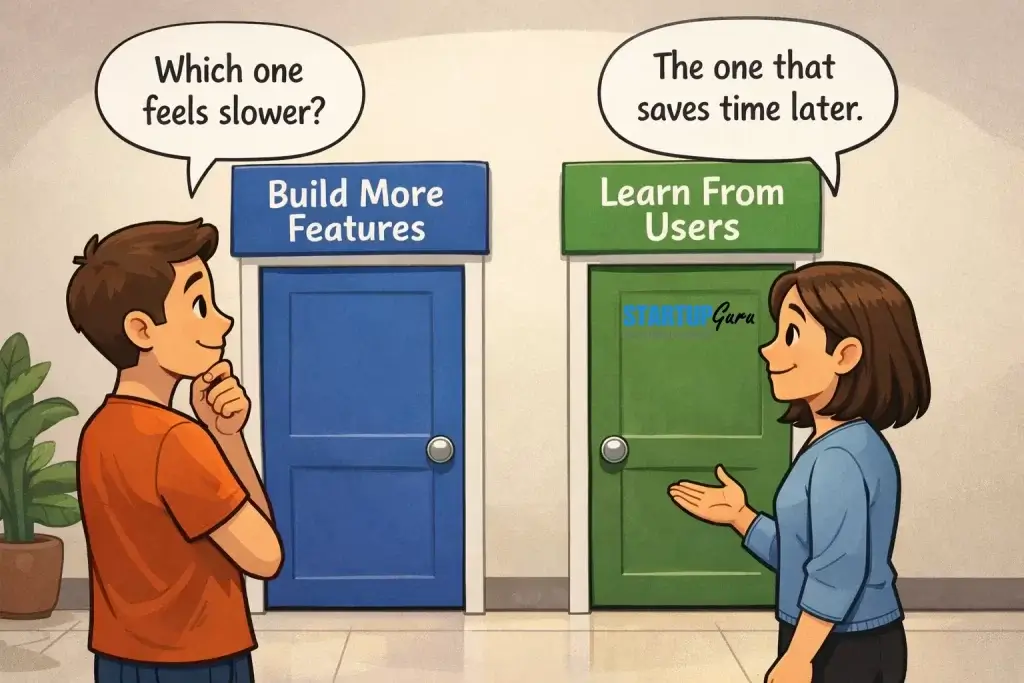

The biggest shift a non-technical founder can make is moving from a build-first mindset to a decision-first mindset.

Founders who succeed tend to stay closely involved in defining success metrics, even if they never touch the code. We’ve seen this involvement change the outcome of MVPs dramatically.

An MVP is not something you “hand off” and wait to receive. It works best when the founder stays deeply involved, not in technical execution, but in shaping the questions the product is meant to answer.

That starts with user behavior, not features.

Instead of asking what the product should include, it is more useful to ask what a user should be able to do, understand, or decide after using it. Clear user journeys often reveal that many planned features are unnecessary at this stage. What matters is whether the core flow works and whether users move through it without friction.

Validation should be defined before development begins.

This is where many MVPs quietly lose direction. Non-technical founders often wait until after launch to decide what success looks like. By then, development momentum makes it hard to pause or change course. Clear validation criteria up front, even simple ones, create discipline. They turn feedback into data instead of opinions.

Another important principle is reversibility.

Early product decisions should be easy to undo. This applies to features, design, and technology choices. Non-technical founders do not need to understand the details of architecture, but they should insist on approaches that allow change without major rework. This keeps the MVP flexible and reduces the fear of making the “wrong” choice too early.

Iteration should be deliberate, not reactive.

Real user feedback is rarely clean. Some users ask for more features. Others use the product in unexpected ways. The role of the founder is to interpret patterns, not respond to every request. Iteration works when changes are tied back to the original assumptions being tested, not when they are driven by the loudest input.

It also helps to treat MVP development as a learning loop rather than a timeline.

Build, observe, measure, adjust. That cycle matters more than how fast you ship. Studies on early-stage product development consistently show that teams who structure learning cycles outperform those who optimize only for speed. Speed without direction usually just gets you to the wrong place faster.

For non-technical founders, this approach restores control.

At StartupGuru, the strongest results came from founders who treated MVP development as a series of decisions, not a one-time build.

You may not write code, but you decide what matters, what gets tested, and what happens next. When MVP development is framed this way, it stops being intimidating and starts becoming manageable.

Different Ways to Build an MVP Without a CTO

Once non-technical founders accept that they do not need to rush into a technical co-founder decision, the next question becomes practical. How does an MVP actually get built without one?

There is no single right path. Each option comes with trade-offs, and understanding those trade-offs matters more than choosing the “best” option on paper.

Freelancers are often the first route founders consider. They are accessible and appear cost-effective. Freelancers can work well for narrowly defined tasks or short experiments. The risk shows up when product thinking is required. Most freelancers execute what is asked. They rarely challenge assumptions or help structure validation. If the founder is not clear on scope, the MVP can quickly become fragmented.

We’ve seen freelancers work extremely well when scope was tight and learning goals were clear, and fail completely when founders expected product strategy along with development.

MVP development agencies offer structure and delivery capacity. For non-technical founders, this can feel reassuring. Timelines, teams, and processes are defined upfront. The downside appears when agencies treat MVPs like full product builds. Without a validation-first mindset, agencies may optimize for output rather than learning, leading to overbuilt MVPs that look impressive but answer very little.

Technical advisors and mentors sit at a different layer. They do not build the product, but they help founders think through decisions. This can be valuable when paired with another execution model. On their own, advisors rarely move the product forward. Their impact depends heavily on how involved they are and how well founders act on guidance.

Fractional CTOs bridge some of this gap. They bring technical leadership without full-time commitment or equity lock-in. For non-technical founders, this can help with architecture decisions, roadmap planning, and vendor oversight. The challenge is availability. Fractional roles work best when expectations are clear, and engagement is structured.

Product-led development partners operate slightly differently. Instead of starting with code, they start with validation, user flows, and decision checkpoints. For non-technical founders, this model often feels more collaborative. The risk here is choosing partners who claim to be product-led, but still default to feature-heavy builds. The distinction shows up in how much pushback they give when assumptions are unclear.

Across all these options, one pattern is consistent.

We have seen that in most cases, founders benefited most when execution was paired with product guidance rather than pure delivery.

The success of MVP development without a CTO depends less on who writes the code and more on who owns the learning. When that ownership stays with the founder, supported by the right structure, the absence of a technical co-founder is rarely the limiting factor.

What matters is choosing a model that keeps decisions transparent, reversible, and aligned with validation rather than speed alone.

DID YOU KNOW?

StartupGuru's incubation program for non-technical founders provides handholding support in building your MSP (Minimum Sellable Product). Learn more.

What Non-Technical Founders Should Look for in a Tech Partner

For a non-technical founder, choosing a tech partner is less about resumes and more about behavior.

Strong partners do not start by talking about frameworks or tools. They start by asking questions that feel almost uncomfortable.

Who is the user?

What happens if this assumption is wrong?

What would make this MVP a failure?

Those questions signal product thinking, not just delivery capability.

One of the most important qualities is the ability to explain trade-offs in plain language.

Every MVP involves compromises. Speed versus flexibility. Custom build versus reuse. Short-term validation versus long-term scalability. A good tech partner does not pretend these trade-offs do not exist. They make them visible and explain consequences without hiding behind jargon.

Pushback is another positive signal.

Non-technical founders often assume that alignment means agreement. In practice, blind agreement usually means disengagement. A partner who challenges unclear requirements, questions feature creep, or suggests delaying certain ideas is often protecting the MVP from becoming bloated. Respectful disagreement is a sign of ownership.

Transparency matters more than optimism.

Early-stage development is uncertain by nature. Partners who promise certainty usually oversimplify reality. Clear scoping, honest timelines, and visible progress create more confidence than aggressive promises. This is especially important when founders cannot independently verify technical claims.

At StartupGuru, one pattern we’ve noticed is that the best outcomes came from partners who were comfortable saying no early, even when it slowed development.

Finally, look for a validation-first mindset.

A tech partner who measures success only by shipping features is optimizing for output. A partner who asks how success will be measured, what learning is expected, and when to pause or pivot is aligned with how MVPs are supposed to work. For non-technical founders, this alignment reduces dependency and increases confidence over time.

The right partner does not replace a CTO. They help you understand whether you need one at all.

Founders often tell us later that the most valuable moments were not when features shipped, but when assumptions were challenged.

What Happens After the MVP Is Built

An MVP is often treated like a finish line. In reality, it is closer to a checkpoint.

Once users interact with the product, new information appears quickly. Some assumptions hold. Others quietly collapse. This is where many founders feel pressure to move fast, add features, or scale prematurely.

Some founders we’ve worked with discovered that their original idea needed a pivot, while others gained confidence to double down. Both outcomes saved time and capital compared to guessing.

The more useful approach is slower and more deliberate.

User behavior matters more than user opinions. What people do consistently tells you more than what they say in interviews or feedback forms. Retention, repeated usage, and drop-off points reveal where the product truly delivers value and where it does not.

At this stage, non-technical founders often gain confidence.

They start recognizing patterns. They understand which decisions were reversible and which ones mattered. They can evaluate technical suggestions more critically, even without coding knowledge, because the product context is clearer.

This is also the point where bigger decisions make sense.

Hiring a technical co-founder. Investing in scalability. Raising capital. Expanding scope. These decisions are easier and less risky after the MVP has done its job. Data replaces assumptions. Direction replaces speculation.

Some founders discover that the idea needs a pivot. Others realize the market is smaller than expected. A few confirm strong demand and move forward with conviction. All of these outcomes are valid. The failure is not changing direction. The failure is committing deeply before learning enough.

For non-technical founders we work with at StartupGuru, a well-executed MVP is not about proving technical capability. It is about reducing uncertainty in a structured way. The MVPs that created momentum were the ones where founders were willing to pause, reflect, and adjust before scaling.

When that happens, building the next version of the product becomes a choice, not a gamble.

And at our incubation program, the next step is going to the market and getting your first users. Right, this is not that ‘perfect’ product you’d dreamt of, but that’s not the point. There is a reason we call it MSP (Minimum Sellable Product), as right after we build your MVP, it needs to sell and sell now. Otherwise, none of this matters.

FAQs: MVP Development for Non-Technical Founders

Many of these questions come directly from conversations we’ve had with non-technical founders during early-stage MVP planning. Across multiple MVP engagements at StartupGuru, the same concerns tend to surface, regardless of industry or geography.

No. You need to understand the problem you are solving, the user you are solving it for, and what success looks like at an early stage. Coding is an execution skill. Product clarity is a founder responsibility. Many successful non-technical founders never write code, but they stay closely involved in product decisions.

There is no fixed timeline, but most MVPs that are built with a clear validation goal take a few weeks to a couple of months. When timelines stretch much longer, it is often a sign that the scope is unclear or that the MVP is being treated like a full product too early.

The right budget depends on what you are trying to validate. An MVP meant to test a single core user behavior should cost far less than one designed to support multiple personas or workflows. Founders get into trouble when they set budgets before defining learning goals. Cost follows clarity, not the other way around. Still, if you must crave for a number, here are some ballparks based on what we have seen:

- MSP (Minimum Sellable Product): $5K (learn how)

- Readymade Solutions (see our products list)

- Cloud-based license: Under $1K

- Self-host domain license: $2.5K to $5K

- MVP: $10K–$40K

- Full-featured platform: $50K–$150K+

Costs vary depending on features, complexity, and integrations.

A prototype shows how something might work. An MVP shows whether it actually works in the real world. Prototypes are useful for feedback and alignment. MVPs are useful for validation and decision-making. Non-technical founders often confuse the two and expect validation from something that was never meant to produce it. Learn more – MVP vs MSP vs Prototype

In some cases, yes. No-code tools can be useful for testing simple workflows or internal tools. The limitation appears when custom logic, scalability, or performance becomes important. The decision should be based on validation needs, not trends or convenience.

If your MVP is trying to satisfy multiple user types, solve multiple problems, or support edge cases early on, it is probably too big. A good MVP feels slightly uncomfortable because it forces focus. If everything feels covered, learning is usually delayed.

Focus on behavior, not vanity metrics. Activation, repeat usage, drop-offs, and completion of core actions matter more than downloads or sign-ups. The goal is to understand whether users get value, not whether the product looks popular.

After you understand what you are building, why users care, and what technical challenges actually matter. Hiring too early often leads to misalignment. Hiring after validation leads to clearer roles and better long-term outcomes.

No. An MVP that disproves an assumption early can save months or years of wasted effort. The failure is ignoring what the MVP reveals or continuing to build without adjusting direction.

Staying close to the product decisions. Asking why before how. Defining what you need to learn. And resisting the urge to turn uncertainty into features.