I have yet to meet a founder who set out to build a failing MVP.

Every founder I’ve worked with at StartupGuru believed they were doing the right things. They hired developers. They scoped features. They spent money carefully. They launched something that worked, technically speaking.

And yet, many of those MVPs still failed.

Not loudly. Not overnight.

They failed quietly.

Hardly anyone signed up or bought the product. Usage stayed flat. Retention never formed. Feedback was vague. The team kept “improving” the product, but nothing really changed. Eventually, momentum died. Sometimes the startup pivoted. Sometimes it shuts down. Sometimes it just stalled and faded.

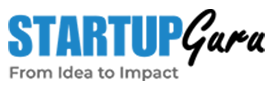

Over the years, working with early-stage founders across SaaS, marketplaces, consumer apps, and internal tools, I’ve seen the same pattern repeat. The failure almost never came down to bad code or weak engineering.

It came from decisions that were already wrong before the first sprint began.

This article is not about how to build an MVP.

It’s about why so many MVPs fail even when they are built exactly as planned.

In this post, we'll cover:

- 1 The Real MVP Failure Problem Most Founders Miss

- 2 Building the Wrong Thing First

- 3 Confusing MVPs With Small Versions of Full Products

- 4 Lack of Clear Validation Goals

- 5 Feature Cramming and Poor Prioritisation

- 6 Letting Technology Drive Product Decisions

- 7 Treating MVP Development as a One-Time Build

- 8 Ignoring Early Signals or Explaining Them Away

- 9 When MVP “Failure” Is Actually Success

- 10 How Founders Can Avoid These MVP Failures

The Real MVP Failure Problem Most Founders Miss

Most founders think MVP failure looks like something breaking.

A buggy app.

A missed deadline.

A product that crashes under load.

That does happen, but it’s not the common failure mode.

The more common failure is far less dramatic. The MVP works. Users sign up. A few even use it. But nothing meaningful is learned, and nothing decisive changes as a result.

At StartupGuru, we often meet founders after this phase. They’ll say things like, “We built the MVP, but now we’re not sure what to do next,” or “Users say it’s good, but they’re not really using it.”

That sentence alone usually tells me what went wrong.

An MVP is supposed to reduce uncertainty. When it doesn’t, it hasn’t failed technically. It has failed as a learning tool.

Kunal Pandya: Chief Mentor – StartupGuru

CB Insights has consistently reported that the top reason startups fail is “no market need.”

What is often missed is that many of these startups did build MVPs. They just didn’t build them to answer the right questions.

I’ve seen founders spend months perfecting onboarding flows before they ever confirmed whether users cared about the core problem. Others focused heavily on scalability discussions for products that had not yet earned repeat usage.

In one StartupGuru case, a founder built a polished SaaS MVP for small businesses. The UI was clean. The tech was solid. The feedback was positive in demos. But when we dug into usage data, almost no one returned after the first week.

The MVP had answered the wrong question.

It proved the product could be built, not that it should exist.

This is where many founders get misled by effort.

When you’ve invested time, money, and energy, it feels like progress must have been made. But learning is not proportional to effort. You can build a lot and learn very little.

Eric Ries framed the MVP as a way to test fundamental assumptions with the least effort possible, not as a milestone to be “completed.”

In practice, many MVPs are treated like deliverables. Once they are shipped, the team moves forward as if validation has happened by default.

This is the real failure point.

An MVP that doesn’t force a decision is not an MVP.

It’s just an early version of a product.

And that distinction is where everything begins to break down.

Building the Wrong Thing First

When founders talk about MVP failure, they usually point to execution. What they rarely examine is selection.

What was chosen to be built first, and why.

I’ve seen this mistake across industries. SaaS, marketplaces, internal tools, consumer apps. The form changes, but the pattern stays the same. Founders start with what feels obvious to them, not what is most uncertain.

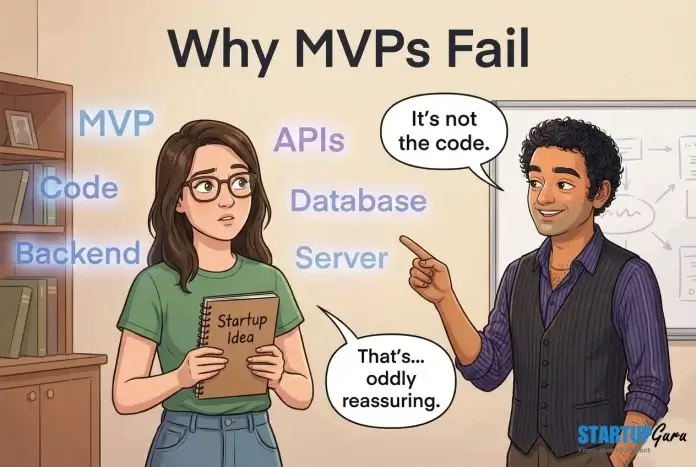

At StartupGuru, we often run product discovery sessions where founders confidently list twenty features. When I ask which assumption each feature is meant to validate, the chatroom usually goes quiet. That silence is telling.

Building the wrong thing first does not mean the idea is bad. It means the order of learning is wrong.

Many MVPs are often based on the founder’s instincts and beliefs. These instincts can come from their experience, deep knowledge of the field, or even personal frustrations. None of these are wrong or unhelpful. However, intuition by itself doesn’t prove something; it’s more like a first idea to test and explore.

The problem begins when hypotheses are treated like conclusions.

I once collaborated with a founder from Seattle who dedicated months to developing sophisticated reporting features. During one of our sessions, he mentioned, “users will definitely want analytics.” However, when we connected with early users, they still found it difficult to complete the main task the product was designed to make easier. The analytics looked great, but they didn’t really address what users needed most.

These lines up closely with what Steve Blank has warned about for years. Startups do not fail because they cannot build products. They fail because they build products without first confirming customer behavior.

Another common version of this mistake is solving a problem that exists, but not urgently enough.

Founders often validate that a problem exists. They talk to users. They hear agreement. But agreement is not an urgency. I’ve seen MVPs where users said, “Yes, this would be nice to have,” and founders interpreted that as demand. After launch, usage stayed shallow because the pain was never strong enough to change behavior.

In StartupGuru’s experience, the MVPs that struggle the most are not the ones solving imaginary problems. They are the ones solving real problems that are not painful enough.

There is also a structural reason this happens.

Founders often choose features that feel impressive rather than revealing. Features that demonstrate capability, not necessity. This makes demos smoother and early conversations more comfortable, but it delays learning.

A revealing MVP is often uncomfortable. It strips the product down to a single question. Will users do this specific thing without being guided, convinced, or reminded.

Most founders avoid that discomfort. Not intentionally, but instinctively.

The irony is that building the wrong thing first often leads to building more things later. More features. More iterations. More explanations. All to compensate for the fact that the original MVP never validated the core assumption.

This is how MVPs quietly fail while staying busy.

And once momentum builds in the wrong direction, it becomes emotionally and financially harder to stop.

Confusing MVPs With Small Versions of Full Products

One of the most damaging misunderstandings I see is the belief that an MVP is simply a smaller, cheaper version of the final product.

It sounds reasonable. It’s also wrong.

When founders describe their MVP as “basically the full product, just without a few features,” I already know how the story usually ends. Not because the product is bad, but because the learning is delayed.

At StartupGuru, we’ve reviewed MVPs that took six to nine months to build and were still called “minimum.” By the time they launched, the founders were emotionally attached, financially invested, and psychologically committed. That makes honest validation very hard.

A full product mindset changes how decisions are made.

Founders start worrying about edge cases too early. They design for scale before there is traction. They polish flows that haven’t yet proven useful. The MVP starts to resemble something that should succeed, rather than something that is allowed to fail fast.

I’ve come across a story about a marketplace founder from Ohio who wanted to have everything ready for both sides of the platform before launching. They created profiles, dashboards, messaging, notifications, and admin tools – everything was functioning perfectly! However, the marketplace was stuck; supply was waiting for demand, and demand was waiting for supply. While the MVP was all set, the essential validation was still missing. It’s a great reminder that sometimes getting things moving is just as important as having everything fully built!

This confusion is partly cultural.

Many founders come from environments where shipping equals success. In corporate settings, finishing a project is the win. In startups, finishing an MVP without learning anything meaningful is often a loss.

Eric Ries has been clear about this distinction, but it’s frequently lost in translation. An MVP is not about minimising effort for its own sake. It’s about maximising validated learning.

The moment you treat an MVP like a product milestone, you start optimising for the wrong things. Design polish over insight. Feature completeness over clarity. Speed over direction.

In practice, the MVPs that work best often feel incomplete in uncomfortable ways.

They do one thing well and ignore everything else. They force users into a narrow path and observe what happens. They generate friction on purpose because friction reveals intent.

This is hard for founders who care deeply about quality. I’ve seen capable founders struggle with the idea of launching something that feels unfinished. They worry about perception. They worry about credibility.

Ironically, those concerns often lead them to build more and learn less.

An MVP that looks like a product is easy to fall in love with.

Kunal Pandya – StartupGuru

An MVP that looks like a question is much harder to ignore.

And that difference explains why so many well-built MVPs still fail.

Lack of Clear Validation Goals

One of the most common questions founders ask me after launching an MVP is, “So… what should we be looking at now?”

By the time that question comes up, the damage is already done.

An MVP without clear validation goals is like running an experiment without knowing what outcome would prove or disprove your hypothesis. You might collect data. You might even collect a lot of it. But you won’t know what any of it means.

We’ve worked with founders who proudly shared dashboards full of metrics. Sign-ups, sessions, clicks, time spent. When I asked which assumption those metrics were meant to validate, there was no clear answer. Activity had replaced learning.

This is not a rare mistake. It’s the default.

Founders often assume that “users will tell us” or “we’ll know when we see it.” In reality, users are inconsistent narrators of their own behavior. They say they like things they don’t use. They complain about features they never needed. They praise ideas they won’t pay for.

Harvard Business School research has repeatedly shown that stated preference and actual behavior diverge significantly, especially in early-stage products.

Without explicit validation goals, founders tend to interpret feedback selectively. Positive comments feel like confirmation. Negative signals get explained away as edge cases. Over time, confirmation bias takes over.

I’ve seen this happen with a B2B SaaS founder who received enthusiastic feedback in sales calls but struggled with retention. Instead of questioning whether the product delivered ongoing value, the team kept optimising onboarding and messaging. The real issue was never tested.

Clear validation goals force uncomfortable clarity.

They require founders to articulate what must be true for the idea to work.

Will users complete a core action without guidance?

Will they return within a specific time window?

Will they choose this over an existing workaround?

When these questions are defined upfront, the MVP becomes a measuring instrument, not just a product.

Another pattern we see is founders launching MVPs with multiple simultaneous goals. Validate pricing. Validate use cases. Validate demand across different personas. The result is noise. When everything is being tested, nothing is.

In our engagements where MVPs succeeded, validation goals were narrow and explicit. One assumption at a time. One behavior to observe. One decision to make.

The absence of validation goals doesn’t make MVPs fail immediately. It makes them drift.

And drift is far more dangerous than a clear negative result, because it consumes time while creating the illusion of progress.

Feature Cramming and Poor Prioritisation

Feature creep rarely announces itself.

It usually starts with a sentence that sounds responsible.

“Since we’re already building this, maybe we should also add…”

I’ve seen MVP scopes double not because founders were reckless, but because they were trying to be thoughtful. They wanted to cover edge cases. They wanted to avoid future rework. They wanted users to feel taken care of.

At StartupGuru, this is one of the most common failure patterns we encounter, especially among first-time founders and teams from structured corporate environments. In those settings, completeness is rewarded. In startups, it’s often a liability.

Feature cramming is usually driven by fear.

Fear that users will not understand the product unless everything is explained in the interface.

Fear that missing features will make the product feel amateur.

Fear that early feedback will be negative if expectations are not met.

The result is an MVP that tries to satisfy too many hypothetical users at once.

I worked with a London-based founder building a healthtech startup, who insisted on building multiple user roles into their MVP because “we’ll need them eventually.” When we later reviewed actual usage, most users never made it past the first role’s core action. The additional complexity didn’t add value. It added friction. In my opinion, that additional waste wasn’t required in the first place!

This is consistent with what product teams observe across early-stage startups. The more decisions a user has to make early on, the less likely they are to complete the primary action. Hick’s Law and other decision-fatigue principles are well-documented in UX research, but they are often ignored in MVPs because founders are focused on coverage rather than clarity.

Poor prioritisation also shows up in how time and budget are allocated.

Founders spend weeks debating secondary features while the core flow remains untested. Developers implement edge cases that may never occur. Meetings revolve around what to add next, not what to remove.

One of the most useful exercises we run at StartupGuru is asking founders to describe their MVP in one sentence without using the word “and.” Most can’t. That inability usually reflects an MVP that is doing too much.

A focused MVP often feels underwhelming to the founder. That’s normal. It’s supposed to.

The goal is not to impress users with breadth. It’s to observe behavior with precision.

When prioritisation is weak, MVPs don’t fail because they lack features. They fail because users don’t know what to do first, or why they should care enough to keep going.

And once confusion enters the product, no additional features can fix it.

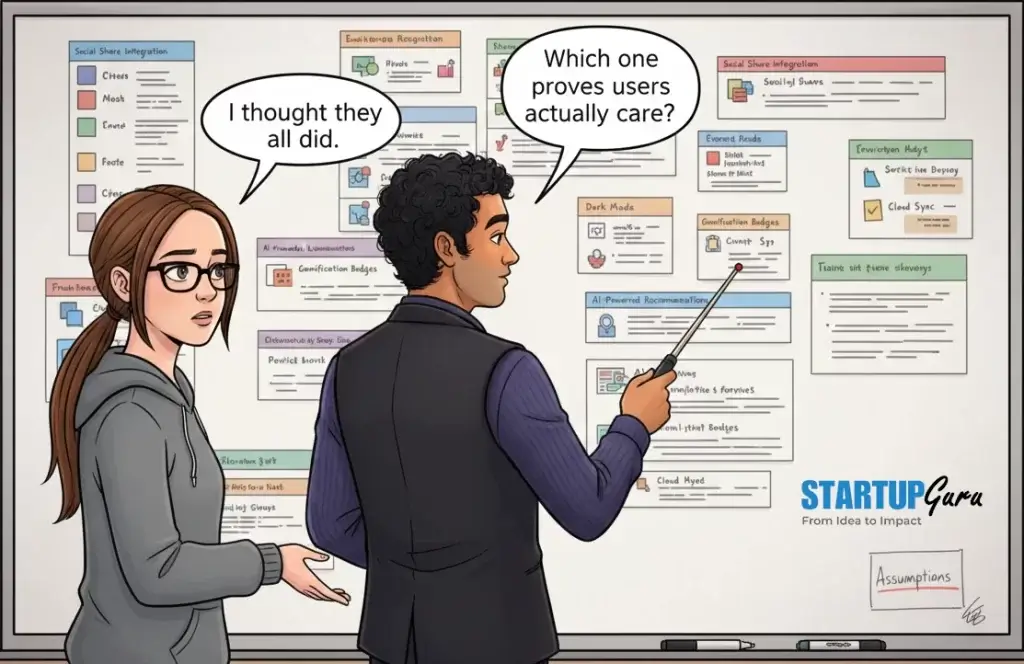

Letting Technology Drive Product Decisions

This is where many MVPs quietly lose their way, especially when founders feel out of their depth.

When you are a non-technical founder building your MVP, it’s tempting to treat technology as an objective authority. If a developer says something is complex, expensive, or “not scalable,” the conversation often stops there. Over time, technical feasibility begins to dictate product direction.

I’ve seen this repeatedly at StartupGuru.

Founders start adjusting their ideas to fit technical comfort rather than user need. A feature is dropped not because it lacks value, but because it is inconvenient to build. Another is added because it fits nicely into the existing architecture.

The product slowly becomes a reflection of the system, not the problem it was meant to solve.

This is not a critique of developers. It’s a structural issue.

Developers are trained to reduce uncertainty in code. MVPs exist to reduce uncertainty in markets. Those are related but not identical goals. When technology decisions are made before product questions are clear, the system optimises for the wrong kind of certainty.

I worked with a Saudi Arabia-based female founder recently whose MVP roadmap was dictated almost entirely by framework limitations. Instead of asking what users needed next, the team asked what the stack could handle easily. Over time, the product became internally consistent and externally confusing.

Premature optimisation is a classic startup mistake, but it’s often misunderstood. It’s not just about performance. It’s about optimising anything before you know it matters.

Donald Knuth’s famous quote about premature optimisation is often cited in engineering circles, but its relevance to MVPs is broader. Optimising scalability, architecture, or extensibility before validating demand creates sunk costs without learning.

Y Combinator has repeatedly advised founders to build the simplest thing that can test the idea, even if it feels inelegant.

Technology should support validation, not lead it.

The healthiest MVP conversations I’ve seen are not about what stack to use, but about what decision a build will enable. When founders ask that question consistently, technical discussions become tools rather than roadblocks.

When they don’t, the MVP slowly turns into a technical project with a product attached.

And those almost always struggle to find real users.

Treating MVP Development as a One-Time Build

Another subtle failure mode is treating the MVP as a phase you “get through” so you can move on to the real work.

This mindset is surprisingly common.

Founders plan the MVP, build it, launch it, and then immediately start planning the next version without pausing to interpret what just happened. Feedback is collected, but not synthesised. Metrics are tracked, but not questioned.

At StartupGuru, we often ask founders to articulate what changed in their understanding after the MVP launch. Many struggle to answer. That’s not because nothing happened. It’s because reflection was never built into the process.

An MVP is not a checkbox. It’s a loop.

Build. Observe. Interpret. Decide. Repeat.

When that loop is skipped, development becomes momentum-driven rather than insight-driven. Teams keep building because building feels productive. Stopping to think feels risky.

I’ve seen founders continue investing in features even when early signals were clearly negative. Low retention. Shallow engagement. No organic usage. Instead of treating these as information, they treated them as problems to engineer away.

This behavior is well-documented in behavioral economics. Once people invest resources into a path, they are more likely to continue, even when evidence suggests they shouldn’t. The sunk cost fallacy doesn’t disappear in startups. It intensifies.

MVPs are supposed to protect founders from this trap by keeping investment small and decisions reversible. But that protection only works if the MVP is treated as an experiment, not a milestone.

When MVP development is framed as a one-time build, failure becomes personal. When it’s framed as a process, failure becomes data.

That distinction changes everything.

Ignoring Early Signals or Explaining Them Away

One of the hardest things for founders to do is listen honestly to what early signals are telling them.

Not because the signals are unclear. But because they are uncomfortable.

I’ve sat in review sessions where founders showed declining engagement curves and then immediately followed up with explanations. “It’s just because onboarding isn’t finished yet.” “These users aren’t our real target.” “Once we add feature X, this will improve.”

Sometimes those explanations are correct. Often, they are coping mechanisms.

At StartupGuru, we’ve seen MVPs where users signed up but never returned. Where they completed the first action but never the second. Where they needed repeated prompting to do what the product was designed to make easy.

These are not technical problems. They are signals.

Ries and Blank both emphasise the importance of actionable metrics over vanity metrics for this reason. Numbers that look good but don’t influence decisions create false confidence.

The danger is not missing signals. It’s rationalising them away.

Founders often believe that persistence means pushing through negative feedback. In reality, persistence without interpretation is just stubbornness dressed up as resilience.

Some of the strongest founders we’ve worked with were the ones who paused early, questioned their assumptions, and made uncomfortable changes. Others kept going, convinced that effort would eventually overcome evidence.

The difference was not talent. It was a willingness to listen.

MVPs fail when founders hear feedback but don’t let it change their thinking.

When MVP “Failure” Is Actually Success

This is the part most founders don’t expect.

Some of the most successful outcomes we’ve seen at StartupGuru came from MVPs that “failed” quickly.

A founder validates that users won’t pay. Another learns that the problem isn’t painful enough. A third realises that the market they imagined is far smaller than expected.

In each case, the MVP did exactly what it was supposed to do.

It prevented a larger failure.

This is the reason we have the “Sellability” part at the core of our incubation program. First Validate, Then Build. We call it MSP – Minimum Sellable Product. MVP is often misunderstood. Changing the term entirely changes the mindset. You need that. Most first-time, non-technical founders need that.

In one case, a Texas founder of a Logistics startup invalidated their idea within six weeks. They were disappointed, but they hadn’t burned through a year of savings. They took those learnings, applied them to a new idea, and built a stronger second MVP that gained traction.

This aligns with broader startup data. Early invalidation saves capital, time, and emotional energy. It also sharpens the founder’s judgment. You don’t lose credibility by changing direction early. You gain it.

The failure is not learning that an idea doesn’t work.

The failure is continuing to build when evidence says it won’t.

How Founders Can Avoid These MVP Failures

Avoiding MVP failure doesn’t require genius. It requires discipline.

Discipline to define what must be true before building.

Discipline to limit scope even when more feels safer.

Discipline to listen to behavior over opinion.

Discipline to stop or pivot when learning demands it.

The founders who succeed are not the ones who build the fastest. They are the ones who learn the fastest.

We have seen this a lot at StartupGuru cohorts; the MVPs that worked shared a few traits. Not checklists, but patterns. Founders stayed close to decisions. They resisted feature bloat. They treated technology as a means, not a driver. They allowed the product to prove them wrong.

An MVP is not a bet on your idea.

It’s a bet on your ability to learn before it’s too late.

And when that mindset is in place, MVPs stop failing quietly. They start doing the job they were meant to do.

For some non-technical founders, clarity comes from reading, reflecting, and applying these lessons independently. For others, it helps to go through this learning process in a more structured environment.

That’s one of the reasons we built the StartupGuru incubator specifically for non-technical founders working on tech or digital startups. The program is designed to help founders learn how to frame MVPs as validation tools, define the right assumptions to test, make product decisions without needing to code, and understand when to iterate, pivot, or stop. It’s not about speeding things up. It’s about reducing blind spots early. Founders can apply to the program and, if there’s a fit, use it as a way to build clarity before committing deeper time, money, or resources.